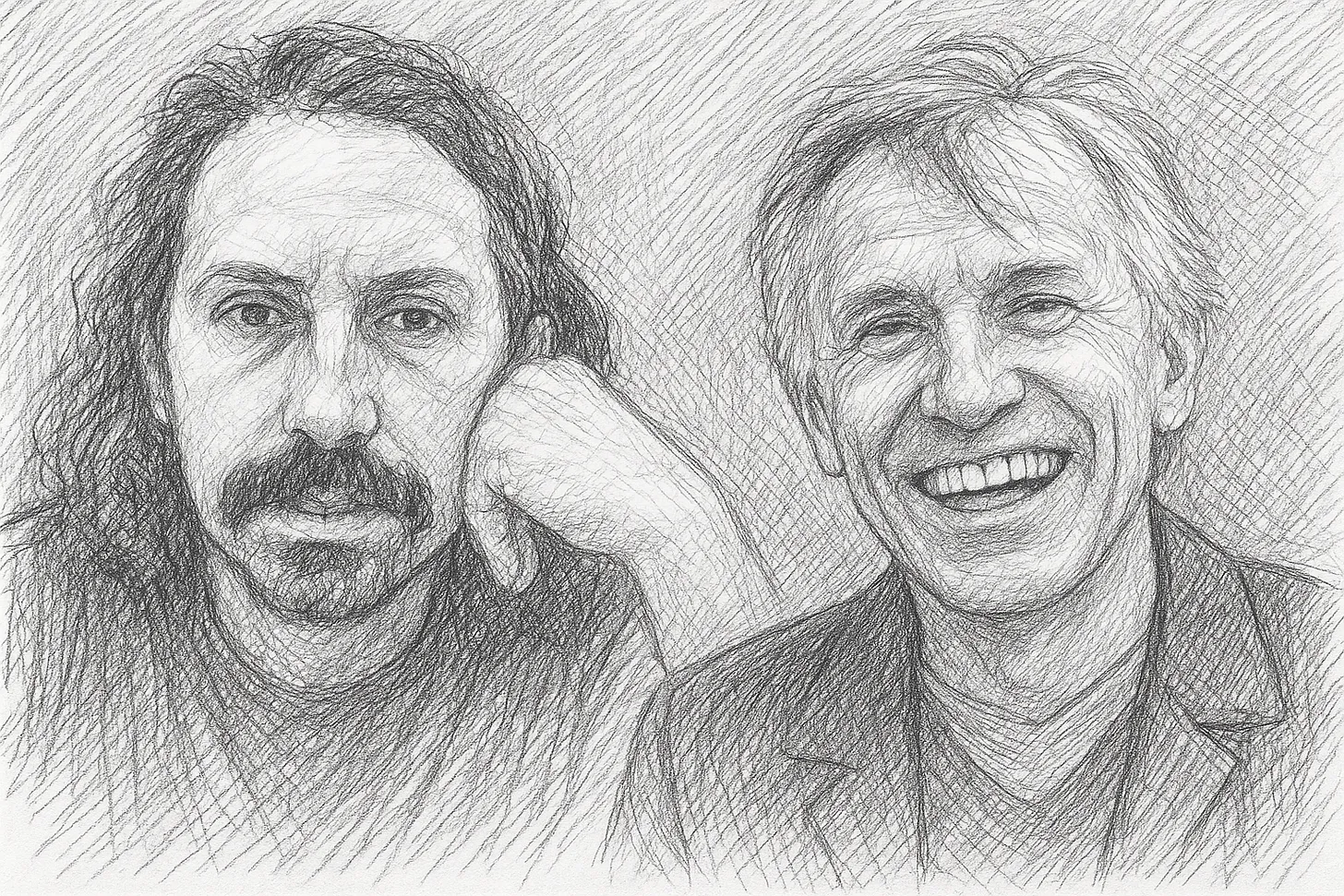

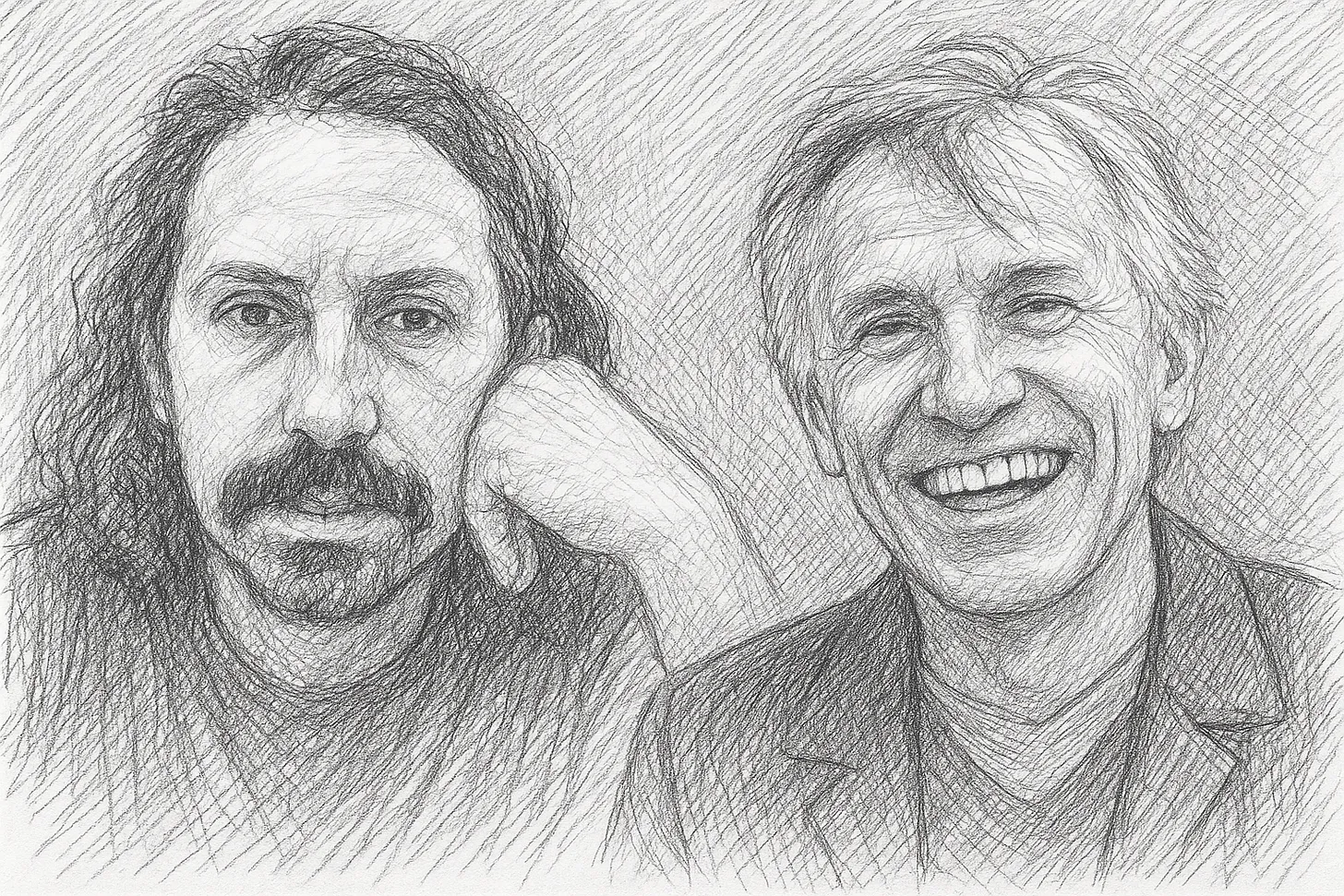

Happiness, Ethics, & Consciousness:

A Conversation with David Pearce

Ludwig Raal: I recently had the pleasure of talking to the British transhumanist philosopher David Pearce. I first came across his work in 2018, when he appeared on Robert Wright’s podcast The Wright Show (now called Nonzero) to discuss transhumanism. At that stage, I only had a vague sense of what transhumanism was, but as David explains below, its central vision is simple: building a civilization of super longevity, super intelligence, and super happiness. Who could argue with that?In 1995, David published an online manifesto he called The Hedonistic Imperative (a playful nod to Kant’s Categorical Imperative), where he makes the case for abolishing suffering for all sentient beings. The radical simplicity of this message appealed to me immediately, and I’ve been following his work ever since. Unfortunately, transhumanism often suffers from an image problem, associated in the public mind with egocentric tech billionaires. But transhumanists are not a monolith. David, for instance, is one of the kindest and most gentle souls I’ve met — motivated above all by the conviction that nothing should suffer. To me, he is the ideal ambassador for the cause.

Our conversation loosely splits into three themes. First, we discuss the pursuit of super happiness and its critics. I do my best to play devil’s advocate by searching for value in suffering, but with little success (perhaps unsurprising given how much I agree with David). From there, we turn to normative and meta-ethics, where I try to tease out possible differences by contrasting my classical utilitarian leanings with his negative utilitarianism.

Lastly, we dig into the topic of consciousness. Consciousness is a notoriously hard topic, and I felt somewhat out of my depth. However, it is also an enormously consequential topic. After all, to abolish suffering, we need to know who and what can, indeed, suffer.

It was an immense honour talking to David, and I hope readers will find value in our conversation.

Enjoy!

David Pearce is a British transhumanist philosopher and co-founder of The World Transhumanist Association / Humanity+. He is best known for The Hedonistic Imperative (1995), which makes the case for abolishing suffering in all sentient life through science and technology. Pearce envisions a future of superlongevity, superintelligence, and, above all, superhappiness.David on X

The Abolitionist Project

The Hedonistic Imperative

SuperHappiness

Ludwig Raal: Maybe to start us off, could you give me your elevator pitch for transhumanism, and exactly what it entails, so we get all our terms right?David Pearce: I define transhumanism in terms of the three “supers.” In a nutshell, transhumanists want to build a civilization of superlongevity, superintelligence, and superhappiness. Each of these terms needs unpacking.

Superlongevity is the idea that aging will ultimately turn out to be a fixable process. Transhumanists aim for an indefinite youthspan and indefinite healthspan, with a backup option for today’s elderly in the form of cryonics, and perhaps even cryothanasia. We don’t yet know how to fix aging, so I think the cryonics option is important. Transhumanism should offer something for everyone, including the old. Whether posthuman superintelligence will want to reanimate Darwinian malware from the previous era is another question — I’m sceptical - but cryonic suspension keeps options open.

Superintelligence: now, that’s something that really does need unpacking. Conceptions of superintelligence range widely. One vision is a Kurzweilian fusion of humans and our machines, including maybe whole-brain emulation or “mind uploading”. On this conception, the distinction between humans and our machines will disappear in the aftermath of an imminent Technological Singularity. For technical reasons I’m personally sceptical of whole-brain emulation.

Another conception of superintelligence is runaway, software-based, recursively self-improving machine intelligence — a so-called “intelligence explosion”. That view is particularly associated with the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) and Eliezer Yudkowsky. Yudkowsky himself has shifted strongly toward an AI-doom scenario. (If Anyone Builds it, Everyone Dies: The Case Against Superintelligent AI (2025) by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares).

My preferred conception is what I call full-spectrum superintelligence: recursively self-improving biological robots — i.e. us — upgrading ourselves, rewriting our genetic source code, cyborgising our bodies, implanting neurochips, so that we can do everything our machines can do and more. But critically, full-spectrum superintelligence, as I conceive it, will also be supersentient. Full-spectrum superintelligence will have a (super)mind - a unified subject of experience - able to explore billions of alien state-spaces of consciousness. By contrast, I believe that no classical digital computer, no implementation of a classical Turing machine or large language model, can solve the binding problem. Our machines are not going to wake up, become unified minds, and explore the realm of phenomenal consciousness.

Superhappiness: the third “super.” I think we have an obligation to replace the biology of involuntary pain and suffering with a more civilized signaling system — life based on information-sensitive gradients of superhuman bliss.

So that’s transhumanism in a nutshell. Of course, each of the three “supers” can be explored in much greater depth than I’ve done here.

Ludwig Raal: All three are interesting, and we might want to return later to the idea of digital minds being conscious, or the possibility of brain emulation. But for now, I’d like to focus mainly on the super happiness aspect.

My first exposure to your work was about seven years ago, when you were on Robert Wright’s podcast. Toward the end of that conversation, you posed a very interesting thought experiment: What if we came across an advanced civilization that had eradicated suffering? Of course, the idea of reintroducing suffering would be absurd.

It was such a neat way of framing the issue, because it really asks people: how committed are you to the supposed virtues of suffering? Some people cling to suffering not just for instrumental reasons, but because they believe it has some intrinsic value.

So why do you think it is so difficult to convince people that negative experiences are, in fact, bad? To me, it seems almost tautological.

David Pearce: Like you, I tend to regard the badness of suffering as almost tautological. It’s very hard for me to “steelman” and adequately engage with people who do see a virtue in suffering.

That said, humans are rationalizing creatures. In view of the frightfulness of suffering, people want some way to make sense of it — to rationalize it, to put the best possible gloss on things. And one needs to tread carefully, because we don’t want to undermine people’s coping mechanisms and the consoling narratives they’ve built around their own negative life experiences.

For a long time I assumed the biggest obstacle to fixing the problem of suffering was ethical- ideological. So I spent a lot of time rebutting objections. Ideological opposition will indeed loom large. But I’m now more inclined to think the biggest obstacle to the abolitionist project is just status quo bias. That’s why I sometimes use what might seem a rather contrived scenario — humanity encountering this alien civilization underpinned by gradients of lifelong bliss, and ask if we’d urge the superhappy aliens to reintroduce ancestral horrors. The scenario forces people to confront their own status quo bias.

And honestly, I doubt more than a tiny fraction of people would seriously urge such advanced aliens to reintroduce suffering.

Ludwig Raal: I suspect you’re right. People tend to rationalize suffering and often attribute meaning to it, probably as a way of coping. And in a sense, coping with suffering is a way of alleviating it. Those people might even be closeted hedonists like the rest of us.

David Pearce: There’s an irony when critics say what counts most is meaning rather than happiness. Because in practice, the absence of a good mood — depression, chronic malaise, anhedonia — tends to drain life of meaning, shading into the nihilistic despair of severe depression. But empirically, the engine of meaning is pleasure. The more intensely pleasurable an experience feels, the more meaningful it seems.

So although transhumanists urge a world of superhappiness, such a world would also be supercharged with meaning and significance simply in virtue of being so intensely pleasurable.

Ludwig Raal: Many people also argue that suffering or bad experiences are necessary in order to appreciate the good — that you need the contrast. But is that really true? Do you really need to suffer a tragedy in order to be happy? From my own observation, some of the happiest people I know are those who’ve never experienced anything especially bad. So it seems like quite a dubious empirical claim.

David Pearce: Exactly. We know that there are, tragically, people who suffer chronic pain or chronic depression — sometimes both. It would be absurd and offensive to tell them, “You’re not really suffering; in order truly to suffer you need to be able to contrast misery with happiness.”

And yet the idea that a contrast with nastiness is somehow necessary to appreciate niceness is surprisingly common. You can’t have the sweet without the sour. I radically disagree. But if hedonic contrast is what some people really want, let the contrast be between pleasure and superpleasure.

For example: today our hedonic range may be schematized as running from -10 to 0 to +10. But imagine instead a genetically engineered hedonic range stretching from +70 to +100. The contrast between +70 and +100 would be immense. Yet even rock-bottom hedonic +70 would still be orders of magnitude richer than our peak experiences now.

So one shouldn’t imagine superhappiness as somehow monotonous. Well-being could be every bit as diverse as one chooses — just without the depths of experience below hedonic zero that characterize Darwinian life.

Ludwig Raal: To be fair to the other side, we should try some self-reflection and steelman their position a little. In everyday life, there might be some value in minor discomforts. These aren’t serious cases of suffering, but sometimes friction can be useful.

For example, in legal processes, I think it’s good that there are some hurdles to divorce. That prevents people from making rash decisions. Or take modern dating culture: swiping apps make it very easy to find “romance,” but perhaps that has devalued it somewhat. Maybe there is value in the discomfort of putting yourself out there in real life.

These are very trivial examples of very minor sufferings. They’re not serious objections to the abolitionist project at large, but I do think it’s worth reflecting on them before we talk about eradicating all negative experiences altogether.

David Pearce: I completely agree. Given our current biology, praise, blame, sanctions, and (rarely) even prison are sadly sometimes unavoidable. But really, it’s a matter of progressively shifting life on Earth to a more civilized signaling system.

Thinking long-term, we should ask: what should be our ultimate goal? Should we keep our existing biology, with its signaling system based on the pain–pleasure axis, or should we move to a pleasure–superpleasure axis?

I know that sounds like science-fiction. But we can learn from existing humans at the extreme high end of the (Darwinian) hedonic scale — I’m not thinking of dysfunctional bipolar mania, but rather, hyperthymia, people with very high hedonic set-points. Studying extreme hyperthymics can give us insight into the extraordinary blessings - and the potential pitfalls - of creating an entire hyperthymic civilization.

And yes, I’ll admit: just occasionally I feel a desire to cause a little bit of suffering — not in a vengeful way, but for example when a meat-eater scorns veganism and says, “Bacon, yum!”, or “But I like the taste!” Part of me wishes animal eaters could gain just a hint of what, say, a factory-farmed pig experiences, so they’d reconsider. But essentially, the goal is still outright abolition of all experience below hedonic zero, with information-signalling hedonic dips functionally analogous to the mental and physical pain of Darwinian life.

Ludwig Raal: I suspect that some critics of transhumanism aren’t actually opposed to the abolitionist project itself. They might also want to abolish suffering, but they’re sceptical of the way transhumanism proposes to do it — namely, through technological interventions.

In The Hedonistic Imperative, if I recall correctly, you outlined three possible paths to super happiness: pharmaceuticals, some form of virtual reality, and then your preferred method — rewriting the human genome to elevate our hedonic set points while still maintaining our preference architecture.

First, did I summarize that correctly? And second, do you see why some people might find that prospect dystopian?

David Pearce: I think of our options via a crude trichotomy: wireheading, psychopharmaceuticals, and genome reform, or more snappily, genes, drugs or electrodes.

Reading about “wireheading” as a kid first alerted me to the possibility that it might be technically feasible to get rid of suffering altogether. Wireheading involves intracranial self-stimulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system — stimulating what were once called the “pleasure centers” of the brain, though they’re probably more accurately described as “desire centers.” Rats given the option to self-stimulate keep pressing the lever endlessly, showing effectively no tolerance, until they collapse from exhaustion.

That’s one conception of a world without suffering: uniform happiness through direct neurostimulation. But most people are repulsed by this idea — partly because it involves rats, who carry a negative cultural image, but partly because wireheading seems to make a mockery of human relationships, culture, and everything else we find valuable.

The second family of options is psychopharmaceuticals: not street drugs, but true “supersoma” — a perfect pleasure drug. In Huxley’s Brave New World, soma was actually presented as shallow and flawed, but let’s assume that medical science can develop a richer version of soma that sustainably elevates hedonic set-points, shows minimal tolerance, and gives everyone a much higher default quality of life. That would be the second family of scenarios for fixing suffering.

The third family of options, and the one I favour, is genome reform. Instead of medicating children from birth with “super-soma,” we should aim for higher innate default levels of well-being — raising hedonic set-points by modifying our genetic source code. Increasingly, that’s the direction I’ve tilted toward. Drugs are just a stopgap.

We don’t yet have even a passable imitation of soma. All existing pleasure drugs have severe drawbacks. Still, I think it would be absolutely wonderful if medical science could come up with (super)soma. About half of people today with clinical or subclinical depression still aren’t adequately treated by current lame antidepressants. We need something better — but even the best drug would only be a sticking-plaster solution.

In the long term, genome reform is key. Even tweaking a handful of strategic genes could immensely reduce the burden of misery worldwide — in humans and non-human animals alike.

Ludwig Raal: It’s unfortunate that Huxley wrote soma to be imperfect, which made it an easy idea to ridicule and dismiss. But in principle, if happiness were guaranteed — if you were pacified by being constantly happy — that doesn’t strike me as a self-evidently terrible thing.

David Pearce: Well, yes. In Brave New World, soma even had some of the attributes of MDMA (Ecstasy) — the “hug drug.” There’s a scene in the novel where the Deltas are rioting because their soma supplies had run out; and once they were sprayed with soma, they all ended up hugging each other.

On a side note, I find it disappointing how little progress there has been in clinical psychopharmacology over the past 30 or 40 years, especially compared to the rapid advances in AI. One likely reason is that the neurotransmitter system most involved in hedonic tone — the mu-opioid system — is also the one most associated with addiction and abuse. That creates a huge obstacle to developing safe, effective mood enhancers.

Even the word “antidepressant” sounds depressing. I prefer terms like “mood brightener” or “mood enricher.” Psychiatrists use a trichotomy: dysthymia, euthymia, and hyperthymia. But it’s not even clear what euthymia — supposedly “normal” healthy mood — really entails. At best, Darwinian humans have a mediocre conception of mental health.

Ludwig Raal: Some of the scenarios you sketched out seem to risk triggering people’s “reality bias.” If you look at the popularity of films like The Matrix, or people’s instinctive revulsion toward Nozick’s “experience machine,” it seems most people prefer a messy reality over a fake but pleasant one.

Do you think that preference is purely descriptive, or do you think it has any normative justification?

David Pearce: In a world with profound existing problems, the idea of slipping into Nozick’s Experience Machine and living happily ever after seems morally repugnant. We ought to fix the world first.

Yet once we have tackled those problems, what then? Personally, I can’t see any problem with entering an Experience Machine once our ethical duties have been discharged in basement reality. Indeed, I’d love to enter one in my dotage! Immersive virtual reality has fallen somewhat out of fashion compared to the immense hype a few years ago, but I still think it’s quite likely that many of our successors will spend most, if not all, of their lives in immersive VR.

The beauty of hedonic set-point recalibration, however, is that it allows us still to engage with (what passes as) consensus reality — the “real world” - but with a much higher baseline quality of life. Such hedonic uplift is not irresponsible escapism in Nozick’s sense, but neither is it just accepting the old hedonic treadmill with its low default hedonic set-points.

Ludwig Raal: Yes, I suspect that’s why, even though rewiring the human genome sounds quite invasive, it has the advantage of conserving people’s desire for “real” experience. In a way, your preferred method works with people’s existing biases, which I hope will help it gain traction.

David Pearce: I hope so too. When I talk about “rewriting” the human genome, realistically editing will begin with just a few genetic tweaks. Eventually we will indeed be able comprehensively to rewrite genomes, but for now, even tweaking a handful of key genes — those involved in pain processing and hedonic tone — could go a long way to civilizing the world.

Ethics

Ludwig Raal: If you don’t mind, I’d like to shift gears a little and explore some more normative and meta-ethical issues. From your work, I know you identify as a negative utilitarian — but I don’t recall you ever explicitly invoking negative utilitarianism in The Hedonistic Imperative.When I read it, I found myself in furious agreement with most of what you said. I’ve always considered myself more of a classical utilitarian. And in practice, I think negative utilitarians and classical utilitarians overlap a lot. Take Peter Singer, for example — probably the most prominent advocate of classical utilitarianism. Yet his work almost exclusively focuses on eliminating suffering: addressing global poverty and campaigning against factory farming. He does this, I think, for practical reasons: because eliminating suffering is where we can make the greatest gains.

By contrast, you also focus on eliminating suffering, but you seem to do so for normative reasons — not just practical ones. Could you expand on that, and perhaps justify it?

David Pearce: Yes. There’s a big issue for negative utilitarians here. The most intuitive way to naturalize value, if one is some kind of value realist, is through classical utilitarianism. For the pleasure–pain axis seems to disclose the world’s inbuilt metric of value and disvalue. Thus suffering - my suffering - is self-intimatingly bad. The badness of my agony isn’t an open question.

But if that’s true, isn’t pleasure self-intimatingly good?

This poses a critical challenge for negative utilitarianism.

That said, consider Ursula Le Guin’s story, The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. Recall how the city of Omelas is a place of fabulous delights. But for unspecified reasons, its happiness depends on the torment of a single child locked in a basement. The citizens of Omelas know about this child, and they accept the arrangement as the price of their joy. Effectively, they are classical utilitarians. Child abuse is a price worth paying for big enough bliss. As a negative utilitarian, I would walk away from Omelas. Even the suffering of “just” a single child is a morally unacceptable price to pay for immense happiness.

Yet what does “walking away from Omelas” entail? Here things really do get controversial. Negative utilitarianism is often associated with the “compassionate world-destroyer” argument: if all that really matters is ending suffering, then wouldn’t the right thing be to destroy the world cleanly and be done with it?

Even as a thought-experiment, life lovers are appalled at the counter-intuitive implications of negative utilitarianism; but the implications of classical utilitarianism can be at least as unintuitive and cataclysmic if followed through. The fact that something is intuitively disturbing doesn’t mean it’s wrong — after all, the implications of quantum mechanics are deeply disturbing and counterintuitive too. Will the objectively correct theory of ethics - if such there is - be any different? Every value system has some deeply counterintuitive implications.

Take classical utilitarianism again. It seems to mandate an apocalyptic, civilization-destroying “hedonium shockwave”: i.e. converting all matter and energy into pure bliss, optimized as “hedonium,” presumably spreading AI-assised at near the speed of light. And that’s one of the less disturbing implications of classical utilitarianism — others are nastier.

Here’s a thought-experiment: imagine a genie offers me super-exponential growth in my pleasure at the cost of an exponential growth in your suffering. As a classical utilitarian, I must accept this offer as an excellent trade-off, since the super-exponential growth of my pleasure far outweighs your exponentially increasing suffering. But of course, the prospect is morally obscene.

As a negative utilitarian, I would decline the genie’s offer.

Non-philosophers sometimes dismiss these kinds of scenarios as “just thought-experiments”. But in ethical theory as distinct from science, thought-experiments are crucial — just consider the endless variants of the trolley problem. And there are moral dilemmas far more serious than tradeoffs with trolleys.

So yes, I accept, negative utilitarianism has counterintuitive implications. The most famous is the benevolent world-destroyer argument. I’ll be frank: if there were a hypothetical off-switch for all suffering, I would press it — even though in practice I advocate (on negative utilitarian grounds) enshrining the sanctity of life in law.

But perhaps the most counterintuitive implication of negative utilitarianism is this: imagine a blissful utopia, as wonderful as you can conceive, marred only by the threat of a single pinprick. Would it be worth painlessly obliterating that entire civilization to prevent a pinprick? At face value, that prospect seems absurd.

And yet, what about a bit more pain than a pinprick? What about a very mild toothache? Or short-lived moderate suffering? At this point, everything gets very messy. Pure negative utilitarianism gets diluted into a theoretically inelegant negative-leaning utilitarianism. As I said, every ethical system has counterintuitive implications. Part of me thinks: if you’re not prepared to accept all the implications of your own preferred theory, then you need a better theory! Modify or abandon it. But biting the bullet is extremely uncomfortable.

In the pinprick scenario, I would argue that anticipatory distress caused by the spectre of obliterating everyone’s lives and dreams is far worse than the pinprick itself. Everyone should feel safe. So on NU grounds, the pinprick should be permitted. But this line of reasoning still needs more fleshing out.

Ludwig Raal: If I had to compare the two extreme scenarios of both views — on the one hand, an eradicated world with no life, and on the other, a world transformed by a utilitronium shockwave — I’d bite the bullet for the shockwave.

David Pearce: Me too. But there are blissful civilization -preserving alternatives less counterintuitive than a utilitronium / hedonium shockwave. Thus we can imagine a richly complex, genetically reformed civilization based on information-sensitive gradients of superhuman bliss surrounded by vast expanses of hedonium. Strictly, such a scenario wouldn’t involve absolute maximum cosmic value everywhere, because of the bubble of “merely” superhuman gradients of bliss in the ocean of hedonium; but such a blissful future could be arbitrarily close to maximum cosmic value as conceived by classical utilitarianism.

Making such compromises, especially when they don’t involve important moral costs, strikes me as a pragmatic way forward. One reason why some thoughtful negative utilitarians avoid dwelling on hypothetical world-destruction thought-experiments is that such thought-experiments needlessly alienate potential allies. You don’t need to be a negative utilitarian to think we should phase out the biology of involuntary suffering. But if you start by acknowledging, “Yes, I would press the off-switch,” to end suffering, you immediately lose a large potential constituency of support.

Consider how pain-free surgery became standard: using general anesthesia didn’t require a consensus among moral philosophers, or indeed surgeons. Surgical anaesthesia just became obviously good and accepted as the right thing to use. Scattered religious opposition to anaesthesia lasted little more than 15 years. I think the same will be true of eliminating involuntary suffering, albeit on a longer time-scale. As the tools of mood-enrichment mature, lifelong well-being won’t win immediate acceptance from everyone. But eventually, a totally pain-free life underpinned by gradients of bliss will be regarded as common sense, as natural as breathing.

Ludwig Raal: For now, then, we can set our minor theoretical differences aside and be allies in the pursuit of information-sensitive gradients of radical bliss.

But let’s, perhaps, linger on negative utilitarianism for a bit longer. I assume you must be quite sympathetic to antinatalism. I’ll admit, I used to be sympathetic myself, but over time I’ve come to find Benatar’s asymmetry argument (see below) less convincing. Some of the intuitions he asks us to accept don’t seem well motivated.

Scenario A (X exists)

Scenario B (X never exists)

1. Presence of pain (Bad)

3. Absence of pain (Good)

2. Presence of pleasure (Good)

4. Absence of pleasure (Not bad)David Pearce: I would describe myself as a “soft” antinatalist. I don’t think one is morally entitled to bring more involuntary suffering into the world. But for evolutionary reasons, antinatalism isn’t going to solve the problem of suffering. Involuntary childlessness itself causes a great deal of suffering. So I see antinatalism as something of a distraction from fixing the problem of suffering itself.

I admire David Benatar’s moral clarity. Unfortunately, Benatar also doesn’t really engage with the selection pressure argument: the practical effect of being an antinatalist is simply that anyone predisposed to stay child-free removes themselves from the gene pool, exerting further selection pressure in favour of natalism. Baby-makers will always outcompete the childfree.

Ludwig Raal: Right. But I do think Benatar makes a questionable move when he says that the absence of pain is good, while the absence of pleasure is not bad. That seems to smuggle in the conclusion he wants. But I don’t see why I cannot consider the absence of pleasure as bad when he considers the absence of pain as good! Either they are both neutral, or they’re good and bad respectively.

I know he’s famously private — partly for security reasons, perhaps, but also because he doesn’t want his philosophy to be psychologized. Still, I can’t help but think temperament plays a big role in whether you find his two key intuitions compelling: that the absence of pain is good, while the absence of pleasure is merely neutral.

David Pearce: I sympathize with Benatar’s desire for privacy. His arguments stand or fall independently of his personal circumstances. That said, I think all futurist visions run the risk of being a form of disguised autobiography to some extent. It’s a bias to guard against. In my own case, suffering has loomed large: I struggled with depression when I was younger, and my personal narrative has been one of trying to overcome low mood. I’ve been able to banish the melancholia, but not the (mercifully incomplete) anhedonia. But that’s not everyone’s experience. Most people are not clinically depressed, or even sub-clinically depressed. Life lovers often have very different narratives, though even the best Darwinian lives have tragedies and disappointments.

Transhumanism in particular is predominantly a movement of optimists and life lovers. Life is good. The greatest fear of many (most?) transhumanists is death, and their narrative is about fighting aging and mortality.

As for David Benatar, I doubt the security angle is really significant — I don’t imagine antinatalists are potential assassination targets. But I do very much respect his wish for privacy. Personally, when I watch a podcast, I find myself focusing on people’s tone of voice, appearance and mannerisms rather than just their words. Studying speakers gives me the illusion that I understand what they are saying better. Presumably, people do the same with me - a bit alarming. But such personal trivia are also a distraction: ideally, surely one should focus on the content of what is being said, not the incidental details of delivery. And yet there’s a tension, because after observing someone speak, one does often feel one understands their ideas more.

Ludwig Raal: Well, in our case, your views will be judged entirely on their merits — since this will only appear in written form, you’ll be relieved to know.

Let's switch gears again, from normative ethics to meta-ethics. I know you’re a moral realist, or at least you used to be. Do you still hold that view, and could you make your case for moral realism?

David Pearce: Consider suffering. Its badness is, I think, self-intimating. If you are in agony or despair, it isn’t an open question whether the agony or despair is disvaluable. There is a built-in normative aspect to the experience.

Now, an anti-realist might respond: “Well, yes, no doubt your suffering feels disvaluable to you, but there’s nothing contradictory in my saying that I think your suffering is good. There is no objective fact of the matter”.

I would suggest that this response simply expresses an epistemological limitation on the part of the value anti-realist. If the antirealist could directly access my suffering, maybe via use of a reversible thalamic bridge to do a partial “mind meld”, then s/he would experience its inherently disvaluable nature - and act accordingly.

Science teaches us to embrace the “view from nowhere” or alternatively phrased, the “view from everywhere”. If we take such a God’s-eye view, then all here-and-nows are ontologically on a par. My reasoning is that, given suffering is intrinsically disvaluable for me, suffering is intrinsically disvaluable for any sentient being anywhere. There is nothing ontologically special or privileged about me. My being special is a genetic fitness-enhancing illusion.

The badness of my suffering induces me to withdraw my hand from the fire. A notional God-like full-spectrum superintelligence who could access, and impartially weigh, all first-person perspectives would figuratively withdraw the hand of all sentient beings from the fire, so to speak. Compare mirror-touch synesthetes today, who experience the disvaluable pain of others as if it were just as disvaluable as their own.

The hardest part of this case for value realism is explaining what is meant by saying that suffering has a built-in normative aspect. How is collapsing the is-ought distinction consistent with physicalism? Well, I am a monistic physicalist who believes in the (ontological) unity of science.

This takes us into very thorny philosophical territory: the nature of the physical, and the notorious Hard Problem of consciousness. In brief, I’m a non-materialist physicalist. To solve the Hard Problem, I suspect we need to transpose the entire mathematical apparatus of modern science onto an idealist ontology. Experience discloses the intrinsic nature of the physical. The nature of the physical includes states along the pleasure–pain axis, which have a built-in evaluative component.

Now, you either take the so-called “intrinsic nature” argument seriously as a solution to the Hard Problem or you don’t. All proposed solutions to the Hard Problem of consciousness are extremely implausible — this is simply the one I find most credible. Non-materialist physicalism may turn out to be true or false, but if it’s false, I fear the Hard Problem will be insoluble to the human mind.

Consciousness

Ludwig Raal: Yes, I’d like to explore consciousness a bit more. And again, I know it’s a bit boring, but perhaps we need to define our terms. I assume that both you and I use Thomas Nagel’s conception of consciousness: the idea introduced in his essay What Is It Like to Be a Bat?A being is conscious if there is something it is like to be that being. We don’t know what it’s like to be a bat. But if some mischievous genie turned you into a rock and me into a bat, I assume that I would still have some kind of experience — a very strange one, no doubt. But turning someone into a rock would presumably be the same as death, since I assume a rock has no experience.

David Pearce: As an aside, some humans can develop rudimentary echolocation. But that anomaly doesn’t alter Nagel’s central point: it is an objective fact about the world that it is subjectively like something to be a bat (not “like” used in the sense of drawing a comparison, but rather of qualia, “raw feels”.)

Materialist science has no explanation of what it’s like to be a bat. And that’s true of subjective experience more generally. Physicalism best explains the unique technological success story of modern science. Physicalism entails the (ontological) unity of science: life can be explained in terms of molecular biology; molecular biology in terms of quantum chemistry; and chemistry in terms of physics. The Standard Model and General Relativity together explain everything — except consciousness.

For some scientists, this failure is just a little wrinkle or puzzle. But in fact, such ignorance is far-reaching, because consciousness is the only thing one ever knows, admittedly often not under that description. Naïve realism is false: what to each of us appears to be the distant horizon is still part of one’s own skull-bound conscious mind. The real external world is theoretically inferred, not directly perceived. What I’m going to say may sound hyperbolic, but materialist science is inconsistent with the entirety of the empirical (“relating to experience”) evidence. If a materialist ontology is true, we should be zombies. There shouldn’t be any “empirical” evidence at all. And yet science works - in a sense.

This is an almighty problem. How do we close what philosopher Joseph Levine christened the “explanatory gap”? However detailed our mapping of the neural correlates of consciousness, we still don’t know why it is like something to be anything at all. If we discount naive realism, even talk of the “neural correlates of consciousness” misleads. For the patterns of neuronal firings one “observes” under the microscope in, say, surgically-exposed nervous tissue are themselves subjective experiences internal to one’s own phenomenal world-simulation.

Anyhow, if you like I can say a bit more about my preferred solution.

Ludwig Raal: Please do. You’ve hinted at your view already, and I know from other talks you’ve given that you think consciousness might be fundamental in some sense. Does that make you sympathetic to panpsychism?

David Pearce: Well, yes — loosely, you could call me a panpsychist. But the term “panpsychism” suggests a kind of property-dualism, i.e. every fundamental physical property has an inseparable experiential property too. I take a more radical view.

Stephen Hawking, himself a hardcore materialist, famously asked: What breathes fire into the equations and makes a world for us to describe? Physics is silent here. Science doesn’t know. I suspect the intrinsic nature of this mysterious “fire” — the essence of the physical — is experience itself. The mathematical formalism of quantum field theory exhaustively describes the structural-relational properties of the world. The Standard Model in physics is a stunning triumph of theory and experiment.

But what is the intrinsic nature of a quantum field?

Our best clue - perhaps our only clue - lies in the quantum fields comprising our own mind- brains.

I don’t think that the fundamental nature of the world’s quantum fields differs inside and outside the head. What makes animal minds like us special isn’t consciousness per se - it’s the essence of the physical - but rather the way consciousness is bound into unified virtual worlds of experience. Phenomenal binding is the hallmark of mentality, enabling us to run world-simulations that masquerade as the external environment (“perception”).

Non-materialist physicalism is, of course, only a conjecture. It may well be false; and I don’t want to tie the abolitionist project too closely to speculative metaphysics. But it is my working assumption: consciousness holds many mysteries but there is no Hard Problem of consciousness because consciousness discloses the intrinsic nature of the physical. Only the physical is real; only the physical has causal efficacy; and the physical is exhaustively described by the mathematical formalism of physics. Materialists, I think, misconstrue the intrinsic nature of the physical.

Ludwig Raal: I need to tread carefully here, because I may be out of my depth. But I take it your view contrasts with theories like Integrated Information Theory, which many people are drawn to. As I understand it, IIT assumes that consciousness emerges once information processing reaches a certain level of complexity. On that view, many non-conscious elements can, when combined in the right way, give rise to consciousness — a form of radical emergence.

By contrast, the idea that consciousness is fundamental — “consciousness all the way down” — seems in a way more parsimonious, because it doesn’t require this mysterious radical emergence.

David Pearce: Exactly. “Strong” emergence is essentially equivalent to magic. If strong emergence were real, literally anything could happen. Philosophically-minded scientists dislike strong emergence for that reason.

Now, an Integrated Information theorist could still take consciousness as fundamental, while focusing on how to explain complex minds. But that leads us to a problem that I consider almost as fundamental as the Hard Problem itself: the binding problem.

Why aren’t we just 86 billion discrete membrane-bound neuronal “pixels” of micro-experience? Suppose the Hard Problem were somehow solved, maybe by non-materialist physicalism as I propose, maybe some other way. Microelectrode studies using awake subjects tend to confirm that individual neurons support micro-experiences — fleeting mico-flashes of colour, a tone, and so on. Why don’t these micro-experiences remain separate? Why aren’t biological nervous systems just aggregates of what William James called “mind dust”?

After all, 330 million skull-bound American minds are individually conscious, and intercommunicate, but (almost) no one thinks the USA is a unified continental subject of experience. Likewise, the enteric nervous system (“the brain in the gut”) is an incredibly complex information-processing system of some 500 million neurons; but no one thinks there’s a unified “person” in your gut. (Or maybe an integrated information theorist would take this possibility seriously; I don’t know!)

Yet somehow, when you’re “awake”, these 86 billion neurons - or at least a proportion of them - combine into a unified subject of experience — and when you’re dreamlessly asleep, they don’t. That’s what David Chalmers calls the “structural mismatch” between what we experience and what neuroscience describes.

Phenomenal binding is not only mysterious, it’s also hugely computationally powerful and functionally adaptive. One way to see how it’s fitness-enhancing is by looking at syndromes where binding partially breaks down: simultanagnosia, where someone can only see one object at a time; integrative agnosia, where they can’t perceive objects as wholes; or akinetopsia (“motion blindness”), where someone sees, say, a lion first in one spot, then another, then another, but never the lion in motion between them.

Phenomenal binding allows us to experience unified perceptual objects and dynamic scenes. Yet textbook neuroscience offers no explanation of how binding is possible.

Ludwig Raal: You’ve expressed scepticism about the possibility of conscious digital minds. I presume you don’t think there’s anything mystical about the biological substrate per se. So is it not possible that, at some point, we could build a machine that perfectly replicates the human brain — silicon instead of meat — and if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, we should treat it as conscious?

David Pearce: Surely it would indeed be a duck — if it were genuinely a faithful replication. But I’m sceptical about “whole-brain emulations”. I don’t think any implementation of a classical Turing machine, or LLM-style architectures, can support phenomenally bound consciousness. In a fundamentally quantum world where the superposition principle of QM never breaks down, decoherence makes otherwise impossible classical computing — involving discrete ones and zeros — physically possible, but that same decoherence precludes such information-processing systems ever supporting phenomenal unity.

My view is that phenomenal binding is nonclassical. A “Schrödinger’s neurons” proposal - i.e. binding via naively synchronous activation of neuronal feature-processors is really binding via individual superpositions (“cat states”) - is controversial. Intuitively, the CNS is too “warm, wet and noisy” for such vanishingly short-lived superpositions to be relevant to our phenomenally bound minds. But a major figure in neuroscience, Christof Koch, has recently embraced a version of this idea as a nonclassical solution to the binding problem.

I should add that you’ll take quantum mind theories seriously only if you’re already deeply troubled by the question of how phenomenal binding is physically possible. But I don’t think our machines with existing architectures are ever going to “wake up.” It’s not that classical digital computers are incidentally insentient; rather, our machines are architecturally hardwired to make phenomenal unity impossible.

This conjecture about digital insentience has ethical implications: if I’m wrong and binding is classically explicable, and if our machines can support “whole-brain emulations” and/or minds of their own, that would profoundly affect the abolitionist project and much else besides. But personally I’m unworried about that possibility. Consider how our most intense experiences are evolutionarily primitive — orgasm, agony, uncontrollable panic — not subtle logical-linguistic thinking. What is it that would allow digital software mysteriously to wake up? More complex code? Faster speed of execution? I can’t rule it out, but such awakening would seem to require some form of strong emergence — which is indistinguishable from magic. We don’t need to invoke phenomenally-bound consciousness to explain the behaviour of classical digital computers. In short, despite my tentative consciousness fundamentalism, I don’t think AI running on digital computers will ever solve the binding problem.

Ludwig Raal: Hmm. I was about to leave it there, but isn’t that in tension with your resistance to the idea of a utilitronium shockwave? Can such a thing be sentient? For pleasure and pain to exist, you seem to require binding, right?

David Pearce: What is the nature of pure hedonium? We don’t know. A universe made of micropixels of intense pleasure would be very different from a universe supporting large, phenomenally bound “chunks” of superblissful hedonium. “More is different.” - qualitatively different. To work out what a utilitronium shockwave would actually involve, we’ll need to solve the phenomenal binding problem too, not “just” decipher the essence of pure bliss.

Closing thoughts

Ludwig Raal: Do you have any final words? It’s been thirty years since The Hedonistic Imperative. How has progress been? Have you become more optimistic about the abolition of suffering since you first published the book?David Pearce: In The Hedonistic Imperative, I speculated that the world’s last experience below hedonic zero might occur a few centuries from now — perhaps in some obscure marine invertebrate in the deep ocean. I’m still very unclear about timescales. In principle, we can already sketch a hundred-year plan to abolish suffering using recognisable extensions of existing technologies. In practice, however, I doubt such a plan would be sociologically realistic.

Technologically, though, the news has been mostly encouraging. Thirty years ago, cultured meat was pure science fiction. The human genome hadn’t been decoded. Today, cultured meat is slowly emerging — erratically and with plenty of legislative obstacles — but it remains our best hope for global veganism, or rather veganism and “invitrotarianism”, this century. There has also been immense progress in molecular biology more generally.

Back in 1995, I didn’t anticipate the possibility of sculpting evolution via CRISPR-based synthetic gene drives that cheat the “laws” of Mendelian inheritance. Together with super-smart AI-powered nanobots, gene drives could be our best tool for remotely managing the well-being, herbivory, reproduction, and fertility of tens of thousands of sexually reproducing species in terrestrial and marine ecosystems. It’s an incredibly powerful technology.

Another milestone was the birth in 2018 of the world’s first CRISPR “designer babies” At the time, I thought exultantly: yes, everything I had foreseen is coming to pass! But then China wobbled. Instead of launching a reproductive revolution that would have led to selection pressure for ever-happier babies, the project was frozen. The scientist responsible, He Jiankui, was demonized. In the US, the first companies are now offering prospective parents embryo screening for “IQ”, but none are yet offering the service for pre-selecting pain thresholds and hedonic tone; and embryo selection is a painfully slow road to paradise compared to germline editing.

So my feelings are decidedly mixed. As for the reception of The Hedonistic Imperative, the ideas are not unknown, but nor have they hit the mainstream. If an ultrawealthy or influential figure like Elon Musk were to declare, “Let’s use biotechnology to solve the problem of suffering,” the Overton window could shift overnight. Who knows, maybe people would hail it as genius - given our culture’s worship of wealth, power and celebrity. But I’m still waiting.

So yes — a mixture of optimism and frustration.

* * * 1

Classical utilitarianism aims to maximize happiness and minimize suffering. Negative utilitarianism gives special priority to reducing suffering, even if that doesn’t maximize total happiness.2

Cryonics is the practice of preserving people’s bodies (or just their brains) at very low temperatures after death, in the hope that future technology can revive them. “Cryothanasia” is a more proactive version — choosing to be preserved before natural death, under controlled conditions.3

The binding problem is the puzzle of how the brain combines billions of separate signals from neurons into a single, unified conscious experience — rather than leaving us with a jumble of disconnected “pixels” of perception. See more here https://www.hedweb.com/quora/2015.html#categorize4

The mu-opioid system consists of receptors in the brain and body that respond to endogenous opioids (such as endorphins) as well as drugs like morphine and heroin, and it plays a central role in regulating pleasure, pain relief, and reward.5

The so-called "hard problem of consciousness," a term popularised by David Chalmers, refers to the difficulty of explaining why and how subjective experience (qualia) arises from physical processes in the brain, as opposed to merely explaining cognitive functions or behaviour.6

For more on David’s views on non-materialist physicalism, see Non-materialist physicalism7

See Testing the Conjecture That Quantum Processes Create Conscious Experience by Koch et al here:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38920469/8

For more on David’s thoughts on the quantum mind, see Quantum Mind

* * * more interviews

1 : 2 : 3 : 4 : 5 : 6 : 7 : 8 : 9 : 10 : 11 : 12 : 13 : 14 : 15 : 16 : 17 : 18 : 19 : 20 : 21 : 22

HOME

Books

Pairagraph

Eugenics.org

Superhappiness

Superspirituality?

Utopian Surgery?

Social Media (2026)

The End of Suffering

Wirehead Hedonism

The Good Drug Guide

The Abolitionist Project

David Pearce (Wikiquote)

David Pearce (Wikipedia)

David Pearce (Grokipedia)

Quora Answers (2015-26)

Reprogramming Predators

The Reproductive Revolution

MDMA: Utopian Pharmacology

Critique of Huxley's Brave New World

Interview of DP by Immortalists Magazine

Interview of DP by CINS Magazine (2021)

The Imperative to Abolish Suffering (2019)

Interview of Nick Bostrom and David Pearce

Death Defanged: The Case For Cryothanasia (2022)

Interview: What's It Like To Be A Philosopher? (2022)

E-mail Dave

dave@hedweb.com